YNM Ep. #06 How a Navy Vet made his way to Microsoft and a growth mindset

- -

- Time -

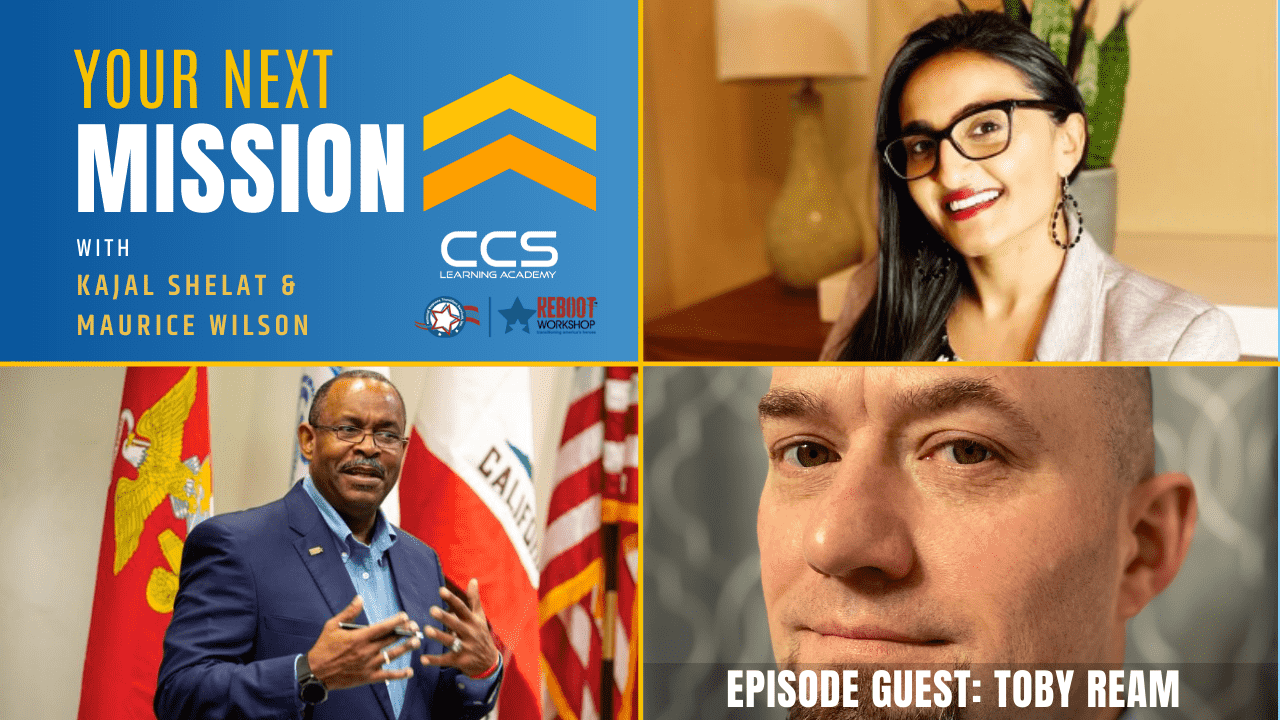

Welcome to Episode #6 of the Your Next Mission podcast! This time we’re talking to retired Navy Flight Navigator, Toby Ream. Toby currently works at Microsoft as a Principal Program Manager in one of their cybersecurity divisions. He shares his transition story, how he found computing, and what’s helped him succeed in today’s tech sector. He’s got lots of great tips! Tune in!

Your Hosts

Kajal Shelat is CCS Learning Academy’s Director of Business Development. She holds a Master’s degree in Business Administration and has 10+ years in the education and professional training sector. She specializes in developing sustainable partnerships and implementing technology training solutions for private and public entities. She uses her passion for education and business to keep our programs current, engaging, and relevant to today’s professionals.

Maurice Wilson is on CCS Learning Academy’s Board of Advisors. A retired Navy Master Chief Petty Officer with 25 years of service, Maurice is the President/Executive Director of the National Veterans Transition Services, Inc. (NVTSI), a non-profit organization he co-founded with retired Rear Admiral Ronne Froman after serving as an advisory member for the Call of Duty Endowment (CODE).

Our Guest

Toby Ream is a retired Navy Flight Officer currently working as a Principal Program Manager in Microsoft’s Sovereign Cloud Security program. With 20 years of infrastructure, security and cloud experience, Toby uses his expertise and natural curiosity to solve hard problems and deliver results through cross-organization collaboration and partnerships at the enterprise level.

Resources from the podcast

Transcript

Kajal: I’m here with Maurice Wilson, a retired Navy Master Chief Petty Officer with 25 years of service. Maurice is the president executive director of the National Veterans Transitioning Services, Inc. and Reboot, a nonprofit organization he founded.

I’m also here with our honorary guests, Toby Ream. Toby is a retired veteran with 25 years of service, 10 years active duty Navy and 15 years Air National Guard. He is a program manager with 20 years of IT infrastructure experience, cloud and enterprise security experience. Currently, he’s focused on scaling Microsoft security for its Sovereign Clouds.

Welcome to our sixth episode, happy to have you both.

Maurice: Hey, it’s good to be here. I can’t wait to learn more about Toby and how his transition is going.

Toby: Thank you for having me Kajal and Maurice. Appreciate the opportunity.

Kajal: As you may or may not know, nearly two-thirds of new veterans say they face difficulty transitioning into civilian life. This podcast is all about helping veterans find their identity after service and offer some guidance, support, some tips, tricks, anything that will be helpful and useful, and how to achieve that.

Toby, I’m going to get right into it. Tell us a little bit about your history and maybe your childhood to start,

Toby: As you’ll learn, I do work at Microsoft, so I want to give a disclaimer. The views and opinions as expressed by Toby may or may not reflect the views and opinions as expressed by Microsoft, just limit their liability.

So you want to know all the way back to my childhood?

Kajal: Yes. I’d love to know a little bit about your background, some of your schooling and then how you got into the service. What was that journey like?

Toby: I grew up in a small town called Cottage Grove, Oregon. I don’t know as if there was anything really special about my childhood. It’s just a small town in middle of the Pacific Northwest. It was a logging town. What got me interested in the military was Top Gun. The original, because the second one hasn’t come out yet. Tom Cruise, you know obviously so Maverick and Goose. At the time, I didn’t realize that you had to have 20/20 vision. Of course, I wanted to be Maverick only to find out I don’t have 20/20 vision so I’d have to make do with Goose. That’s really what got me into it.

My brother brought in an Air Force Academy liaison officer when I was in junior high. They were asking questions about, you know, could he make it to the Air Force Academy. But we’d gone from a private school back into public school and the transition was pretty brutal. He didn’t qualify, but we got in front of my career far enough that after my ninth-grade year, I told my dad that I wanted to go.

At the time I thought Air Force, cause you think fly and you think Air Force. Dad waited until the end of the summer to confirm, “are you really serious?” And I said, yes. Then we just followed up a very methodical path based upon what the Air Force Academy liaison officer had provided in terms of input to my dad about my brother at the time, and tried to put all the checks in the box to make my resume look good.

Ultimately, I ended up doing so well when I was in swimming – I was a backstroker and went to junior nationals – that the Naval Academy wanted me. So, they ended up reviewing my package. The senior medical officer there reviewed my package overrode what the Department of Defense Medical Examination Review Board (DoD MERB) had put in there, meaning you’re disqualified. He’s like, “this doesn’t look like it’s a big deal. We’ll waiver. you.” I ended up reaching out to both my Senator and my Representative asking to switch my nominations. The representative ended up switching me and I ended up getting accepted to the Naval Academy.

Top Gun being the reason why you know, that sort of going fast, obviously it’s a cliché, but it worked for me, you know? And that’s why I wanted to join the military. My dad is a Vietnam Vet, but he never talked about it. He wouldn’t watch any war movies with us. He would answer questions. He wouldn’t shirk question, but he would never volunteer anything.

Kajal: Did your brother get into the Navy as well?

Toby: He did. And he enlisted in the Air Force. So, he went to college. I came from a very strict background. When my brother got away from my parents, he started partying and of course that isn’t good for grades. So he decided to enlist in the Air Force because the college route that he was taking at the time wasn’t looking so good with all his extracurricular activities. He served around four years.

Kajal: You have a family of Veterans. It came within the family dynamic. And I think we’re all pretty influenced by Tom Cruise movies. I’d love to hear a little bit more about your time in the military and your career. What was that journey like??

Toby: I graduated the Academy. Although at one point in time, I remember going to the chaplain and telling him I wanted to resign. They wouldn’t let you resign unless you’d spoken to the chaplain. I remember him saying, “well, what if you regret it?” And I’m like, “hell yeah.” I was just so overwhelmed at the time. It was my freshmen. They call it plebe year. But I ended up not quitting. Glad I didn’t quit.

So, I graduated. I received the very last billet for Naval flight officer. I remember two guys behind me, the captain of the baseball team, he didn’t get it. (I hope he’s not listening to this) I ended up grabbing the last billet.

I graduated and went home for about seven months because although they were short, they also just didn’t have a pipeline that could support this. So, I was doing recruiting at home, working with the local recruiters, which is kind of interesting because recruiting for an academy is not really something you do. I went to a lot of college fairs with them and answered questions and then ended up moving to Florida. They still didn’t have a slot for me so they put me in charge of the uranalysis program. I ran that until I officially started flight school.

I spent I don’t know how many months in flight school and then I had Selected – at the time they called it jets or props. I chose props, which is non-carrier-based aircraft. I was sent from Pensacola after I graduated to San Antonio, Texas. It was a joint program so all Navy and Air Force navigators were going through the same pipeline. That was the 562nd flight training squadron. I earned my wings there.

My Navy wings. were signed by an Air Force Lieutenant Colonel. Interesting. I selected the P3 Charlie, which I think has been decommissioned. There might be one or two squadrons left, but they’re transitioning that to the P8-something that Boeing is making. I went to Jacksonville, Florida for my training specifically in that aircraft. After that, I was stationed in Barbara’s Point, Hawaii where I did three and a half years. I deployed to Japan and the Middle East.

Following that tour, I was assigned to Okinawa, Japan. I was there in support of the P3 mission. I learned about information warfare in Okinawa because the officer in charge had gone to Navy postgraduate school and he had a class in it. I learned a little bit. He couldn’t tell me a lot about it because it was classified. but what he did tell me got my mouth started watering. So, I tried to transition to that but from 1993 to 1996 they didn’t even have enough people to fill all the navigation slots. They were unwilling to let me move. I ended up resigning and it was because I wanted to do a different job.

Kajal: When you left, did you think about what was your next move? I mean, I’m sure it was a bit overwhelming to kind of think about that next transition piece. What was that like?

Toby: My brother built my first computer and I just started playing video games. That’s what really got me into tech. But the funny thing is back then, when you were playing video games on the PC were constantly having to adjust something because nothing ever really worked. You ended up learning a lot about the computer.

I ended up building a bunch of computers and when I arrived in Okinawa, I decided I want to get out. The question is, what do I want to do? It was that discussion about information warfare that began to slowly steer me towards security. I knew I wanted to something in tech, although it was just aspirational at the time. I started building computers at home learning about it. I built a network, I ended up getting some of the Microsoft certified engineer credentials. I got that in 2000 workstation and server.

But I had computers that I was networking. I ended up drilling a hole in the wall with my neighbor. We networked his, we did land parties, but it also taught me a lot about how to connect networks. I had a modem that I connected and networked between all the different computers. I could use it like a network even though it was only a modem. I think I was at 56K.

So that’s how it started out. Just learning on my own. Once I told my boss that I wanted to move into that direction, I did have an opportunity to do some work with some schools in Okinawa and do some volunteer work and whatnot, and actually work in it. And then I was able to transition into the maintenance shop where we ran our exchange server so I was getting some hands-on and some management experience in that field while I was still the Navy. That’s what I did to try to make my resume robust.

You have to realize I was getting out post-9/11 right after the bubble which was certainly not an ideal time, but that’s sort of what I did the,

Kajal: Your transition seemed like a lot of self-study. A lot of self-motivation. What was it like getting into your first job out from there? What, what was that like? Especially given the circumstances, a lot of tough times. How were you able to navigate?

Toby: To be honest, it was brutal. I felt like a failure. I got out In October, 2002. I had 60 days of terminal leave. Then I went through approximately two months of unemployment. So that first Thanksgiving back in the States I was unemployed and then I got a three-week contract. I ended up being honest and telling them I finished all the stuff they asked me to do in two weeks, four days. They’re like, “oh, see you later.” I went into Christmas unemployed and then another two months of unemployment. But the folks on that contract remembered me and in February I was brought back. Then in May. I was hired by the prime on that contract. From there, thankfully I’ve not been unemployed since, but it was a lot of hard work. I mean, being unemployed, especially in this age of the internet where you can apply to stuff at any given point in time, it’s pretty brutal. And the self-talk that’s going through in your head and feeling like a failure and whatnot. Balancing that I think is incredibly hard.

Kajal: Yeah. Maurice works with veterans, veterans transitioning every single day. Is this something that you hear frequently?

Maurice: Absolutely. Have a whole lot of comments and questions Toby. I spent some time at Brooks Air Force Base in Texas, you know, Navy going there to do some learning and education. I ended up there for aviation physiology tech school. My first duty station was, guess what? Barbara’s Point Hawaii. When I finished my tour there, I stayed in Hawaii for about three and a half years. Then I came back to California to Pendleton and then guess where else I ended up at? In Okinawa. It’s almost like we were following each other’s career.

It was so interesting because that was around the 80’s and it was the advent of computers and PCs. You remember, we went from a Tirade and Commodore and started getting into computers and the Z-100s and the whole nine yards. So, I was sort of thrust into technology. I remember one day I was at camp Pendleton and a bunch of Z-100s arrived on the loading dock. We were all standing around looking at all these weird boxes with this thing, this PC and none of us knew anything about it.

The commander at the time was standing there, scratching his head. You know, he had his kind of finger in his ear. Like you don’t know what to do with these things. He looked around at everybody and after 30 minutes of just staring at these boxes, he said, “well, Petty Officer Wilson, I guess you got a new project.” Everybody walked away, left me there on the loading dock. I did what you did not knowing anything about computers. I went and got a screwdriver and took the thing apart to see what was going on inside. That started my whole career.

I wanted to throw that out there because you threw some breadcrumbs out there and I said, “oh man, I can so relate to what he’s talking about, man. I’ve been there, been there, done that.”

I have a question for you. I noticed that you, started out as a Naval aviator for 10 years, then you switched over to the Air National Guard. Together you did a total of 25 years? What caused that decision? What happened there?

Toby: I gapped my service. I exited the Navy in October, 2002. I didn’t join the National Guard till May, 2004. And time? I think it was out maybe six months. My cousin called me out of the blue and he’s like, “they’re starting an information warfare, aggressor squadron down in McCord.” And I’m like, “oh my gosh, that sounds so awesome.” Then I stopped and I’m like,” I’m not qualified for that.” I literally said that on the phone to him. “so, you’re going to say no.” And I’m like, “Okay, good point.” So, I applied. And one thing the military is good about is you have an aptitude for something they’ll actually train you. I nailed the networking question and that’s about it out of the 10 questions they asked me, because it was a technical interview. There’s a little bit about leadership, but they weren’t as crazy about that as they were like, “does this person have an aptitude for the technical?” Cause even in 2004, it was still new. We were doing basically script kitty hacking, which was pretty brand new at the time. They were looking for someone who could learn. And I nailed that one question. Other than that, I showed, I had an aptitude and they accepted me and it wouldn’t have happened if I had said no to myself.

Maurice: You were in the Air National Guard from what, 2004 to what? 2019. Is that about right?

Toby: Let me look across here 2020. I retired last August 20. You can’t see I have a goatee now, so I finally have my requisite facial hair to show that I’m retired, but yeah, it’s just a little over a year now. I’ve been retired.

Maurice: I was listening to your story when you, ended up in Pensacola and you didn’t have a billet, so basically as one of those, what do we do with him? I don’t know. Let’s find something

Toby: That’s it. Hurry up and wait. Right. We know it’s going to happen someday, but we’re not ready yet. What are we going to do? And yeah, nothing like a little urinalysis to motivate an aspiring aviator.

Maurice: It made me think about when I left Long Beach. I was stationed on board the USS New Jersey. They closed down the ship yards and retired the ship and all that. I was looking for the next exciting billet, you know, “what am I going to do after being on a battleship?” Cause there’s hardly anything that could replace that. I figured I was a hospital corpsman, so I’d love to go and work with those guys.

I got the dream orders, I showed up and guess what? They didn’t have a billet for me. The guy, before me got the orders, but the detailer, the records, they forgot to take it off the screen so I showed up and they had the same challenge with me: “Gee, what do we do with him?” Fortunately, because I was a corpsman and they had a need at the branch medical clinic at Naval Training Center, I was able to get diverted over there. I had to bring that one up, you know,

Tell me, when you got out the first time, you said you were unemployed for about one or two months or something like that?

Toby: Yeah. One or two months unemployed, three weeks of a contract. Good gig. And then another two months. So total four months unemployed.

Maurice: Here’s the question and this is going to be relevant to the listeners: It wasn’t because you lacked any skills, right?

Toby: No.

Maurice: You have plenty of skills and technically you could have got a job almost anywhere. Would it be safe to make that statement?

Toby: Depending upon the type of job you want, depending upon where you were willing to go, absolutely. I had a security clearance. I had people calling me from the east coast and they were like, “Hey, I see you’ve got X clearance”. And I’m like, “where are you calling from? Sorry, the answer is no.” So, I self-limited.

So yes, I didn’t necessarily have to accept unemployment, but I chose to go into a field that had a glut of folks because the dot-com bubble had burst. Right. It’s not like I had a lot of experience. And I wanted to stay in the Pacific Northwest. I grew up in Oregon. I wanted to come back to this area

Maurice: You answered my question. For many veterans – and here’s the point I want to make for a lot of the listeners out there – sometimes we self-impose limitations. I want people to realize that Veterans are not necessarily hurting for employment opportunities. Employers want to hire us. There is no tomorrow, however, we’re looking for the right fit. Things have to be lined up pretty much perfectly for us to say, “that’s the job that I want. That’s where I want to go. Because it’s a fit for me.”

Just a footnote for some of the listeners: Every year the Pentagon spends close to a billion dollars on unemployment insurance. Close to a billion dollars on unemployment insurance. And that’s at a time where jobs are plenty. Veteran unemployment is at its lowest. Actually, veteran unemployment is lower than the civilian unemployment, especially now with COVID. I think our number from DOL Vets Department of Labor veteran employment training services is somewhere around about 2.6% where the national average unemployment rate is 3.8%. And then when you look at it by age for older individuals, obviously the unemployment rate is lower, especially like in your case, as an officer, with a degree, with experience, you gotta to have companies just basically beating the door down to get to you. And if you have a security clearance, oh boy, they’ll give you their first-born child to get you to come work for them.

But some of the younger transitioning service members and veterans, their unemployment rates are a little bit higher, somewhere closer to like 12%. So as Kajal said before, a vast percentage of individuals leave the military without employment. Knowing what you know now and having gone through some of the challenges that you went through, what advice would you tell the listeners out there?

Toby: is this in terms of doing it differently or just like talking about how I attacked it at the time?

Maurice: Perhaps your perspective because you it’s going to be different for everyone. You said something, I thought that was really key about your circumstances. You can get a lot of job offers, but if it’s not the right salary, if it’s not the right location, if it’s not the right amount of work, if it’s not the right driving distance… I really want people to understand that the decision for employment isn’t as simple as just getting a job. There are many factors involved in that decision.

Toby: Now to clarify, I didn’t have any job offers. I took my first job offer. I had a lot of inquiries and I killed it because I didn’t want to move back east. But no job offers. I literally took the first job offer. Otherwise everything you’ve said is correct. To be transparent, I didn’t know what I wanted to do in terms of how do you translate what you do into civilian-speak, right? I read the book What Color is Your Parachute to try to identify in there. There were exercises to go through and they said, “well, based upon your answers we believe these are some careers that you might find to be helpful.” I found project management to be something that was closest to what I did, although we used different terminology.

That was the other thing I realized. I spoke military and then within military I was speaking a dialect of the Navy, which is by the way, very different from the Air Force or Army. Like my title. I’m a Naval Flight Officer. What the hell is that right? If you’re not Navy, if you’re a hospital man, and you’ve never been in aviation, you may not even know what that is. And you were in the Navy, right? So that’s something you got to go, “well, how in the world, I translate that job over into, something that corporate America understands?” How often have you seen Randolph Air Force Base on a resume? Where the hell is that? Right? Just put the city and state. Don’t put the actual name of the base someone may or may not understand. The job title; I was the Logs and Records Officer. Oh my gosh. I don’t even know what the hell that is. That’s what I realized from What Color is Your Parachute? I mean, it started, “here’s what I want to do.” And then I was like, “okay, let’s, let’s go after something that’s project management.” Then I realized the more I learned, I did a lot of that in, the military. I just didn’t use those terms. Logs and Records Officer could be project manager.

That was the beginning of learning to actually speak like corporate America speaks. And I didn’t know, I spoke a foreign language. Then obviously finding the job was difficult. I’m not saying everyone does. I see folks who are double-dipping. They still have 60 days of terminal leave and they’ve already started their next job so it’s a much easier transition, but not everyone experiences it. Some folks go through what I went through or worse.

I was able to leverage my Naval Academy connection to solicit an informational interview. It was in those informational interviews. I must’ve done 20 over the course of time. And then I would go back home and I would realize, “oh, I need to work on this.” And that was what helped me to understand. I was speaking a different language because those folks, they did speak my language. They weren’t necessarily Naval Academy. They could have been any academy, but they spoke corporate America and they slowly but surely gave me pointers. I had to follow that bread crumb trail and slowly update my resume and begin to learn how to speak a different language and make sure my resume said the same.

Maurice: In essence, you had to relearn how to speak and talk to civilians and others. Then you had to rebuild your career from where you were. You have to rebrand yourself.

Toby: That’s a very nice way of putting it. Yeah, correct.

Maurice: Actually, that’s what we do at Reboot. We help Vets relearn, rebuild rebrand. It’s remaking, yourself. It goes back to what Kajal said: Two-thirds of Vets face difficulty making the pivot from military to civilian life. There’s a struggle with identity, which is the culture, the language and things of that nature. But then again, there’s that other issue that you pointed out: What do I want to do? I have to pivot but I’m not certified. I need to go back to school and relearn everything.

Toby: I think everyone has to make the decision for themselves. I did not get a Master’s. I did get a couple certifications. I find coming from Microsoft that certifications are helpful for going into a contracting gig where you work for the government. When you’re in like an Amazon or whatever, the only thing those would do for you is maybe break you out from another candidate. We care, more about experience than we care about what’s on paper.

But again, if you’re just comparing two resumes, it certainly can break you out. It’s not going to hurt you. I would certainly not lean upon education or certifications as a panacea. There is no one catch-all. I think everyone has to evaluate what’s the best decision and path for them as they’re doing that transition.

Maurice: That is so true. And this will be my last question and then I’ll pass it back over to Kajal. Obviously, there’s a lot to do to transition from the military to civilian life. Would you agree to that?

Toby: Yeah. You don’t realize it until you’re in the thick of it. And you’re like what? In the world? Yeah.

Maurice: It’s not as simple as just taking off the uniform and then bam, you’re a fit for whatever’s going on. You have to plan it out. This is a major personal self-project that requires long-term planning. My final question is that being the case, when should someone start planning for their civilian careers?

Toby: I’m going to tell you what I did and what I did differently and answer that question. I’ll also say that some folks have a very easy transition. There are times when what you do in the military has a direct translation and people are looking for you and boom, and it’s easy. God bless him. This podcast is not for them. This is for the rest of us.

I went through a really interesting situation. Not everyone goes through what I went through, but unemployment shook me up really hard. If I were to do it differently. I would start probably two years out. Meaning you’ve got to start early. You’re like, “what in the world?” Now I also wouldn’t tell anyone in the military I’m getting out until you literally drop that paperwork. Cause you never know when you’re going to change your mind. You do not want to project that because boy, you could lose opportunities. I remember I was thinking of getting out of the Guard and I know that’s just a part-time job, but things changed and next thing you know, I’m staying in and that was another nine years.

You never know one day everything’s going to hell. The next day could be a new day with the sun shining and you change your mind. You just never know. Do not make decisions that could close doors. I don’t want to say regret just closed doors. Don’t close those doors. Keep them open right until the very last second. Cause obviously when you drop your paperwork, it is what it is, but I would start early. And these steps work in a cycle. I’ll let you do your branding because I really liked that, but I’ve already forgotten what it was. Like three Rs, I think.

Maurice: Relearn, rebuild and rebrand.

Toby: There you go. I think you need to start to network. If you’re overseas this is going to be insanely hard, which is what it was for me. But if you’re in the United States, go to the closest city. Once you figure out what you want to do, I guess that’s sort of the first piece is figure out what you want to do when you grow up and then start networking in those circles.

You can start on LinkedIn. But eventually I’m going to suggest that you really absolutely need to go face-to-face. You’re going to have to network. You’re going to have to find someone who’s in that field and learn more about that field. You may have to iterate because you’re like, “oh no, I don’t want to do that.” Okay. Try this other thing. Then get into networking there. Figure out what that actually is. That’s going to take some time. I don’t think that’s a three-week process, unless you’ve already thought about this. Maybe you already know you want to be a nuclear engineer or a pharmacist or whatever, fine.

If you already know that, then you probably don’t need to do this as much. But for those of us who are going say from infantry or Naval flight officer and detect, which is a sharp departure. Yeah. You need to figure out well, like what in tech? Tech is huge, right? It’s really huge. Do you want project management? Do you want developer? You want to be in AI, machine learning? There’s so much there. Learn how to rewrite your resume. And that’s a hard thing. How to express your experience in corporate-speak. You’ll wish you had the Rosetta Stone or Babble for your resume and it doesn’t exist.

You just have to walk through those steps, in a methodical fashion then learn what programs are available. At Microsoft, they have the Microsoft Software and Services Academy, but if you don’t search for it, if you don’t ask questions, you may not even know if it’s available on your base. If you ask the right questions and you’re inquisitive and curious you’ll start following that rabbit trail and find out where you want to go, but ultimately you got to create a plan for how to shore up the gaps that you identify through: Here’s what I want to do when I grow up. Here’s the network with that person or people. Actually start to educate yourself about what that career is. You go home and see I’ve got a gap there, go shore that up. There’s a nice quote by Seneca that says luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity. Folks at times look lucky, but sometimes it’s because they were sitting there preparing for it. That doesn’t happen overnight. This isn’t a microwave thing that you go two minutes, I’m done.

Maurice: There’s another way of saying that phrase: Chance favors the prepared mind. I want to pass this to Kajal, but I just want to re-emphasize the point that you made, which is start early. Figure out what you want to do then start planning, networking, developing, getting the training. Most people wait until six months prior to separation before they start planning.

Toby: Yup. That is way too late. That’s going to put them in a very awkward position, anything’s possible. but I think what you’ve done is you’ve increased the complexity. You’ve increased the grief and the angsty and the stress. It’s needless. I mean, if you get the right mentorship, if you start looking early enough, then you can alleviate that. Does it increase your stress at the time? Of course, it is. You’re essentially trying to do two jobs, but that’s certainly better than the alternative, which is really painful.

Maurice: Yeah. Yeah, that’s a great discussion.

Kajal: This is great. It’s all about knowing resources as well – and there are a lot of resources out there. A quick Google search is great, but knowing your community, asking questions, putting yourself out there – which is very out of the comfort zone – is something that is so valuable and it’s easy to do. We all get out of our comfort zones a little bit in order to find the path and find our identity.

I want to pivot because we’ve got Toby who had years of IT, infrastructure, cybersecurity background. And we know now that cybercrime is up about 600% since the start of COVID. I’d love to know a little bit about what a typical day is like as a cybersecurity professional. I know you’ve got a lot of you can’t disclose in your line of work, but for those who are potentially looking into getting into cyber or security, or IT in general, would that day look like?

Toby: I’m a program manager so I am going to give you what a day looks like through the eyes of a program manager. Being a manager offers a totally different day, but I’ll go backwards in time to give you a sense of what it looked like. Specifically, I’ll give you Microsoft.

I joined about eight years ago and I was a Security Champ. They called it Privacy Champ and Compliance Champ. I was offered the interview because I knew the person. This goes back to networking because of the Air National Guard. My job at T-Mobile and my job at Microsoft I got the interview ws because I knew the hiring manager in the Air National Guard.

When I got hired I thought I knew so much about security, Because I had literally hacked computer networks or maybe not done every little last piece myself, but I knew how to do it. I’m thinking I understand security. Then I moved into the cloud and I also moved in at an enterprise level that made the Air Force networks that I dealt with in the Air Guard looks small. I had to relearn.

I think really you have to embrace a growth mindset. It’s something you hear Satya Nadella, the CEO of Microsoft say, and I’m going to tell you it was probably four to five years before I truly understood it. I actually read the book Mindset by Carol Dweck. I was at Microsoft for years plus before I read it. I had been listening to Satya talk about it and then realized, oh my gosh, I had such a fixed mindset coming from the military.

In general, it’s what do you do? Take your VAP score to see if you qualify? And then that number seems to hang over your head like a halo for the rest of your career. It’s as good as you were on that day that you were stupid, maybe you were out drinking or whatever you were doing and you didn’t get enough sleep or whatever, suddenly that’s the number assigned to you. And that’s not actually the case. Realize that then that’s what you think about yourself and identify with for the rest of your life. If you make a mistake, if you didn’t get a good score, you are identifying with that.

That is disservice we do in the military. We don’t constantly look to try to fail and learn from our failures. I am an advocate for actually trying and failing and failing fast. It sounds so weird to say you want to fail but we don’t learn when we’re on the mountain. You don’t learn at the top. You learn when you fall down. That is when you actually learn everything. I had to relearn everything I thought I understood. I had to humble myself. Cause I thought I was all that. I had to realize, “man, I need to just go in be humble. Go start asking questions, be curious, realize it’s okay to fail.” Literally relearn that sometimes daily. Like knowing and saying it to yourself versus living it are two different things, it’s easy to say, “oh, go do whatever.” It’s sometimes hard to actually go do it.

I had to ask a lot of questions. My manager was on military leave of absence so I was having to try to figure out how to solicit even mentorship and coaching advice. That was obviously very difficult. Coming into Microsoft was it was my first foray into software. I had. to learn what security was like at an enterprise level.

No matter what it is you think, you know, I guarantee there’ll be something different, something new. And I don’t think it’s about like, what is the technology it’s about? Are you willing to go and learn? Are you willing to ask the right questions, be curious, and then go find out the value you can add? And that’s what I had to go do and be humble about it because where I thought I knew a lot, Kajal, I didn’t know Jack. They did things so differently because they’re doing it in a cloud. Cloud is very different than a standard network so things are done very differently. I think that at a high level I was day in, day out learning and applying that growth mindset. I still have to remember to do that. I still have to remember that. I don’t know anything. Now I’m a manager and you’re like, “well you were a manager in the military.” Sure, but managing IT, managing the cloud. In the environment that I’m in is very, very different. We don’t do a good job of coaching in the military and I have to learn how to coach.

That’s literally something I hadn’t done a lot of, even up until recently. My manager is amazing at challenging me to learn how to do that. So even today, after years of experience in industry, I’m still learning constantly have to embrace that growth mindset, realize, I’m still going to make mistakes.

I remember going to see my manager at my performance review this year and I looked at my bonus and I’m like, “oh wow.” I was surprised. My recollection was I was stumbling and fumbling all over the place. And he’s like, “yeah, you were. And you learn and you changed you redirected. And that’s all I can ask for.”

Kajal: That’s incredible. I have read that book and it is important for anybody, any industry to have that growth mindset. That’s so important and so incredible that you still use that even being in a top level at your organization. Pretty neat.

I want to put you in the hot seat a little bit. What’s your greatest fear right now? Maybe in your career or maybe insecurity or anything that you can think of that is your biggest fear.

Toby: We all have our own personal fears, like who wants to get cancer or something like that. If I avoid all that and just think about would I regret on my death bed or whatever, I think it’s I fear caving into fear and failing without daring greatly.

One of my favorite quotes is from Teddy Roosevelt. It was the excerpt from citizen in a Republic. from Sarbane Paris. There’s a portion of it that says “…who spends himself in a worthy cause, who at the best knows in the end, the triumph of high achievement and who at the worst, if he fails at least fails while daring greatly.”

I don’t aspire to be a CEO or anything. My aspirations are more about giving back to get into a place where I’m blessed and then I can actually go and bless others. And in that, I guess the question is: Will I be able to dare greatly? It isn’t so much about; can I dare greatly at Microsoft and make some sort of achievement financially or whatever. I’m not saying I’m against that. I’m all for that, that helps make your life easier. But I’m really questioning what’s that daring greatly in terms of influencing other people so that when I’m gone from this earth there’s some little nugget that I was able to pass on to others that helps make someone else’s life better.

Kajal: Well, I think the listeners out there will definitely take a lot from what you have said and your insights and the things that you’ve helped along the way.

The next question is what’s your biggest challenge right now?

Toby: My biggest challenge right now is growing as a manager and actually developing my directs. One of the biggest things I’m struggling with is how do I actually differentiate for a direct here’s what level one is versus level two and put it into something that’s actionable. How do I make that actionable so that they can turn that into what the behavior they need to show at level one versus level two so that they can actually show they’re ready. Cause you need to be operating at level two to get there. I haven’t promoted anyone as a manager and that is actually my current biggest challenge. Trying to develop my directs to be their own best.

Kajal: That’s great. What’s your next mission?

Toby: My current mission is being a manager, but I have a passion for veterans. Being a veteran myself, having gone through a really rough transition. seeing folks who wait till six months out and now they’re trying to do this insanely difficult transition, but they’ve already kind of pulled that switch you know, notified everyone they’re getting out. I want to be able to give back something.

The world is not getting less technical. For example, someone at Microsoft, who is a civil engineer by education, took one coding, class, data structures and data algorithms. Then he competed against other computer science degree folks for an internship at Microsoft, beat them and then ended up getting hired, not as an engineer. As a PM. I want to learn how to code so I can show folks how easy it is to actually break in. Even if you don’t want to be a developer learning it helps you to talk to developers and in a better way. That’s I want to do, but I’ve been waiting for my next chapter in my life. We’re building a home in Kirkland, Washington so that’s what’s consuming me right now. Once we move up there and I get to a more stable environment in terms of my time, then I’ll invest in myself so I can get to this.

Kajal: That’s great to hear. Thank you for answering those hot topic questions.

That concludes our sixth episode of Your Next Mission. I want to thank Maurice and Toby for their time and insights today. I want to thank all of you listening out there for giving us your time. If you want more information about CCS Global Tech or CCS Learning Academy, go to our Veterans page. There you can take a tech quiz to see where your technology career path can take you if you are interested in that sector as well. Thanks so much.

Maurice: Thank you. If you want some information about transitioning, go to https://www.nvtsi.org/.